Silence Charumbira recently in Prishtina, Kosovo

My recent trip to Pristina, Kosovo, at the invitation of the European Union’s European External Action Service (EEAS) was pretty enjoyable. It was made even more enjoyable by the fact that the little place has so many similarities with my adoptive home, Lesotho.

Residing in Lesotho, where a good proportion of the population is welcoming, made it seem like I was just at home when I landed in Prishtina.

Yours truly in front of a memorial site in Central Kosovo.

The population, about 1.7 million, is also relatively small, like that of Lesotho with about 2.3 million people. On of the major differences between the two nations is that Lesotho is quite old. It got its independence in 1966 while Kosovo is a young country born in 2008. But in those differences, there lie the similarities as well.

The conflicts in the Balkans, the hardship that the people of Kosovo endured until 2008 appear to have molded their moral fabric.

A brass sculpture in Central Pristina.

The trip was one of my best in recent years, especially after my ordeal with Ethiopian Airlines in July on my way to China. On that trip, the airline lost my luggage and went for months without responding to emails. I ended up going to Or Tambo physically to get a response to my query. And when it came, they said they could not locate my luggage. Therefore, they were offering me a measly RMB1.200 (approximately $170). I thought the offer was a joke, an insult; or both. But that is a story for another day.

At the conference, we were addressed by former Kosovo president Atifete Jahjaga, who advocated free press while lamenting the recklessness with which the media often treats women by focusing on their gender and minor issues like marriage and dressing.

We also had a chance to walk around the small city and appreciate the loads of influences on the people’s culture from other countries in the region among them Italy and Turkey. Those influences add to the great attributes that make the city nothing less than enchanting. Like Basotho, the people of Kosovo love their drinks. They love having fun so much that restaurants are packed from around 10am even during week days.

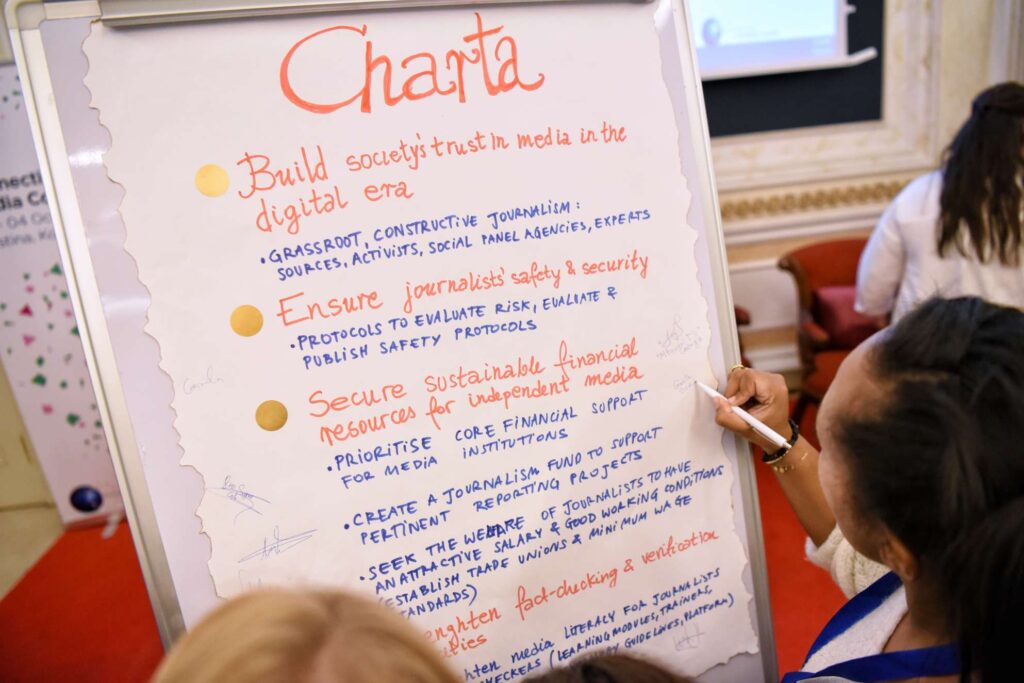

Information in a changing world and information changing the world

The world as we know it is changing, fast. And key to the whole mix is information.

Some of the participants from Africa and the Caribbean

From how it is disseminated, who disseminates it, why it is disseminated, whether or not it is disseminated accurately etc.

But not many people perceive how central and vital the media, as a purveyor of information, is in this whole transition.

From outright propaganda to basic documentation, the media is helping in shaping the affairs and events of the world in both good and bad ways. Sadly, the media space is dwindling, fast. Just before the Covid-19 pandemic, there seemed to have been a consensus that newspapers were dying. After the pandemic, several media outlets shut down. But the need for information remained constant if it didn’t increase.

That need for information was the fuel that social media and other spinoffs needed to thrive. Sadly that has been at the expense of traditional media, especially newspapers. And for Kosovo, that has been even more devastating as the country has been left without a single print newspaper.

In other countries, even the so-called first world countries, newspapers are dying. More are shutting down even now despite the ending of the pandemic.

And that poses even bigger problems not only for the media but for readers, communities, countries and the world at large.

Kosovo-based Gambian footballer, Idrissa Ndow (centre), and some fans

during our tour of Prishtina

The diminishing role of the gatekeeper

Traditionally, media organisations had systems in place in gatekeeping. In my early years in the newsroom, we had older and more experienced personnel who worked as proof readers. Besides the editor, there was a deputy editor, an assistant editor, a news editor, line editors and then proofreaders and sub editors. But now the gatekeeping process is now too expensive.

Newsrooms are struggling to stay afloat and most newsrooms don’t even have line editors and news editors. Fact checking and proof reading, all part gatekeeping, has now been left to editors and in some instances, they are overworked. In other instances, they are inexperienced.

In one of my recent posts, the owner of the business told me an my colleague flat out that we were supposed to do all the gatekeeping on our own because the business did not afford gatekeepers. Between the two of us, we had to produce two newspapers. And by the way, editing often meant rewriting stories, re-interviewing sources, handling interviews and writing some of the stories.

Our experiences are more similar than different

More from Africa News 24

Former Kosovo president Atifete Jahjaga advocates free press

Sadly, this is the new reality for newsrooms all over the world. My experience in Kosovo, a small and young country, was proof of the assertion that media organisations all over the world are facing similar experiences. Since Covid-19, Kosovo has not had a print newspaper. Although journalists have resorted to publishing their content on social media, that too means gatekeeping is regarded excess baggage weighing to heavily on organisations’ wage bills.

What this means is that the quality and accuracy of some of the content is compromised heavily because editors are too busy to be doing the research that’s essential for gatekeeping under normal circumstances. It’s a crisis of monumental proportions.

In comes AI and FIMI

Other journalists who participated in the Kosovo engagement attested that they were facing similar challenges. The problems are worsened by the advent of AI, which has made it easier for anyone to pretend they are a journalist and deliver half-baked news just from a few, simple clicks of a button.

Even bigger a challenge is the fight for traffic and revenue. All businesses must make money. And there lies probably the biggest loophole. Several players – from political to economic – have for a long time been using the media to manipulate the masses. In Europe, they say one of the challenges they are facing is foreign information manipulation (FIMI) from Russia. Media organisations have been compromised by external influences. In Africa, this manifests in the form of propaganda, either by local players or external players.

During the workshop, one of the findings was that AI might be intelligent but in cases where algorithms fall short, they get it monumentally wrong. And while users of AI see it as a saviour that can never be wrong, it can be disastrously wrong. From basics like languages and facts, AI can be royally wrong and it cannot have the ultimate say. It’s information must be verified. Therefore journalists must use it with caution.

Sanctity of the truth

But the truth – outright truth – is the only constant. In the modern day of misinformation, disinformation and other forms of lies, the truth from the media must be outright. It must be complete from every vantage point. And for that truth to be universal, there is need for stronger investment in gatekeeping in newsrooms or otherwise rigorous training for journalists in the values that make their profession sacred.

Once journalists go rogue, the world burns. All the trust, hope even, is eroded.

The truth is the fuel that powers our hope for every coming day. Without the truth, no one, including those in power and powerful countries, can be held accountable for their actions.

Even the wars that are threatening to rip the world apart, threatening to ignite a global war while causing untold suffering in Gaza, Ukraine and other regions of the world.